Aerial photography captures the vivid colors of South Bay salt ponds

Rainbow Fields by Colin McRae. Credit Colin McRae.

For the last eight years, Colin McRae has been flying over the San Francisco Bay Area, photographing the vivid and sometimes surreal colors of the salt ponds in the South Bay. His photograph "Rainbow Fields" was recently featured as "Photo of the Day" on a website for photography professionals, giving Bay Area residents an aerial perspective of the salt ponds hugging the southern shores of the San Francisco Bay.

McRae shoots from a hired helicopter flying at heights ranging from 500 to 5,000 feet, taking off from a variety of small airports around the Bay Area like Oakland, Hayward, and San Carlos. His cameras of choice are the Sony α7R II and Sony α6000 fitted respectively with Sony E 24-70mm F4 and Sony E 18-200mm F3.5-6.3 lenses and polarizing filters.

Continuing a long tradition

The San Francisco Bay Area has a long tradition of aerial photography.

William Garnett

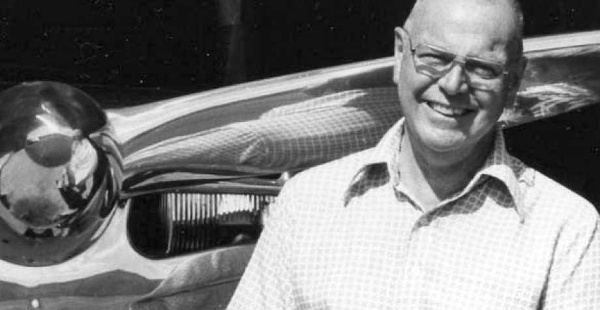

William Garnett (1916 - 2006), a commercial photographer and UC Berkeley professor of environmental design, piloted his own 1955 Cessna 170B plane and took photographs out of a panel cut in the passenger-side floor. He mostly used two 35mm cameras, one loaded with black-and-white film and the other with color, though sometimes he also used a Pentax 6x7 camera.

William Garnett standing in front of his polished aluminum 1955 Cessna 170B plane. Credit The Garnett family.

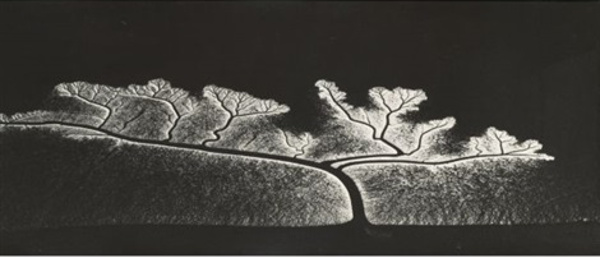

Reflection of the sun on dendritic flow, San Francisco Bay, California, 1963 by William Garnett.

Robert Hartman

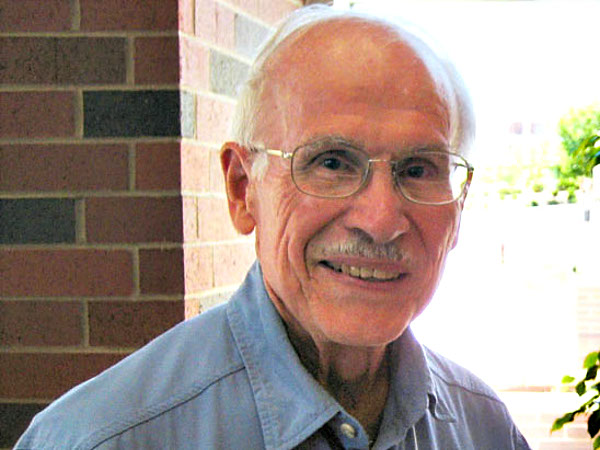

Robert Hartman (1926 - 2015), an abstract expressionist painter and UC Berkeley professor of art, would place his 1949 Piper PA-16 Clipper in a steep bank about 1000 feet above ground level, put the plane's controls between his feet and knees, and point his camera straight down through the open side window. He used special infrared-sensitive film and the Ilfochrome dye destruction print process to give his photographs rich color depth and a unique luster.

Robert Hartman (1926 - 2015), a former UC Berkeley professor of art. Credit UC Berkeley.

Bird with Square by Robert Hartman. Credit Robert Hartman.

Cris Benton

Cris Benton, an architect and a retired professor of architecture at UC Berkeley, mounts his camera to a radio-controlled kite, which can fly as high as 300 feet. The radio can pan and tilt the camera, switch between portrait and landscape formats, and fire the shutter. He watches the camera as it floats above the landscape and imagines what it would photograph. He started kite aerial photography (KAP) in 1984 but it was only in 2003 that he developed an interest in South Bay's salt ponds while taking a series of hikes with microbiologist Dr. Wayne Lanier. After learning about the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project he developed a proposal to continue photographing the South Bay landscape in service of the restoration efforts.

Cris Benton with his Kite Aerial Photography kit. Credit Danny Wilson.

Cargill's salt crystallizer beds at Newark, California. Credit Cris Benton.

Thomas Heinser

Thomas Heinser, a German photographer based in San Francisco, likes to fly over the salt ponds in a hired doorless helicopter close to sunrise, when the light casts long shadows. He uses a Hasselblad medium format camera with a Phase One digital back. A pair of gyroscopes stabilize the camera. Documenting the effects of the drought on California's terrain for the past three years, Heinser's lens has captured the parched texture of the ponds clearly.

Bay Salt 6416, an aerial view of the salt ponds in 2016. Credit Thomas Heinser.

Salt Ponds in the San Francisco Bay

Native Americans produced salt by evaporating the sea water trapped by high tides along the eastern shore of the San Francisco Bay. They used it to flavour their food or trade it with people inland. Rainless summers, a consistent breeze and abundant sun in this part of the country favoured salt production through evaporation. In the 19th century, Spanish and Mexican Californios collected an annual supply of salt for local use in this manner. The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) induced demand on a much bigger scale because of the use of salt to extract gold and silver metal from raw ore. It was in 1857 that bay waters were first enclosed by earthen levees to form salt ponds.

By the early twentieth century, there was a patchwork of small, family-owned salt ponds along the shoreline that was ultimately folded into the Leslie Salt Company. Over time, as real estate in the Bay Area became more valuable, the company started filling in the salt ponds in order to develop them into housing tracts. Environmentalists grew alarmed at the shrinking open spaces along the bayshore. In 1965 Florence LaRiviere, a longtime Palo Alto resident, helped organize a movement towards establishing a national wildlife refuge on the San Francisco Bay. Former US Representative Don Edwards of San Jose, California championed the mission and lobbied Congress to establish a refuge and stop the degradation of the Bay and its wetlands. The process took seven years and in 1972 legislation was finally passed to form the San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

In 1979 the refuge acquired its first salt ponds through condemnation of more than 15,000 acres of property belonging to the Leslie Salt Company. As the condemnation was underway, Leslie sold all of its property to Cargill, Inc., a food giant. The refuge bought the legal title to the salt ponds, but Cargill retained mineral rights, and with them, actual management of the ponds.

In 1985, LaRiviere and other area residents rallied to expand the refuge boundaries from 20,000 to 40,000 acres. She established and led the Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge (CCCR). By 1986, the refuge owned approximately 17,000 acres, most of it the 15,000 acres of ponds where Cargill continued to manufacture and harvest salt. Much of the bay shoreline, though increasingly owned by the federal government, remained a space for industrial production.

Mr. Edwards once again got behind the effort to expand the refuge and ensured the passage of the bill in Congress. President Ronald Reagan signed that measure into law in 1988. In 1995, In 1995, Congress renamed the refuge in Mr. Edwards' honor; it became the "Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge". Between donations of small parcels from conservation groups and transfers of state-owned tidelands and marshes, the refuge expanded to over 25,000 acres.

In 2003, state and federal agencies brokered a complicated and ambitious plan to restore critical wetland habitat for endangered marsh species in San Francisco Bay. The agreement provided tens of millions of dollars to purchase the mineral rights to all refuge lands and some 5000 acres of Cargill’s remaining salt ponds. Over time, refuge managers came to the conclusion that the salt ponds needed to be restored to tidal marshland. The South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project aims to breech the levees and let the tides once again create salt marshes.

Salinity, microbial habitat and vivid colors

The process of salt production begins with filling intake ponds with the bay water which is moderately saline. As water evaporates from the intake ponds, its salinity increases. The more saline water is pumped into another salt pond and the intake pond is filled with fresh bay water. This process is repeated as salinity further increases. It takes three to five years of evaporation and transfers between ten salt ponds to transform sea water at 2.5% salinity into the brine of 30% salinity required to harvest salt.

Salt ponds provide a natural habitat for salt-loving microbes called halophiles. Different halophiles thrive at different salinities and impart their bright colors to the salt ponds.

* Intake ponds at 2.5% salinity tend to be dull green in color.

* At 6% to 16% medium-salinity ponds are bright green in color, with shades of yellow or a fluorescent tint. They contain the Franciscan brine shrimp and Dunaliella salina algae.

* At 18% to 28% high-salinity ponds are red with a purple tint. Dunaliella salina algae produce a red pigment at this level of salinity. Other halophilic bacteria turn the water brown, orange and red with overtones of pink and purple.

* At 30% salinity, ponds are a bright shade of red and purple. Only archae, halophiles that date back to the beginnings of life on earth, can survive in this extreme environment.

Aerial Photography over the Salt Ponds

Interested in taking aerial photographs over the salt ponds yourself? The salt ponds are part of the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, so do keep in mind that there are height and area restrictions on flying over them. The Federal Aviation Authority requests pilots operating fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft to maintain a minimum altitude of 2,000 feet above the surface of the refuge. Since the refuge is a noise-sensitive area, flying any lower than 500 feet is strongly discouraged to reduce potential interference with wildlife. For example, noise from low-flying aircraft may startle nesting birds. Operating drones on refuges is illegal without special use permits.